Learn The Runes

← BackGeographically the runes have been used mostly around Scandinavia, this statement is based upon how many archaeological finds we have from this part of the world. There oldest sources of languages documented in their indigenous language in Europe is Ancient Bulgarian, Latin, Ancient Greek and proto Germanic through the Runes.

Since Scandinavia is the rune’s “home” and since that is where finds go back to the year 0, this post will mainly focus on the Scandinavian usage of these characters. However, we will absolutely show and inform about different runic alphabets other than the ones found in Scandinavia. If you have ever wondered about what runes used to be, what they are used for nowadays and most in between - welcome and enjoy!

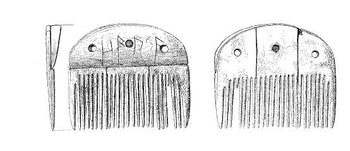

The runic inscription has been translated to the word “harja”, which could refer to the comb’s owner. It has also been theorised to mean “warrior”. The word “harja” has also been found carved on a runestone in Sweden (Sö 32), this stone dates back to around the 5th century. Even though the earliest finds of this language are from the 2nd century, we can assume that the runes are much older, since the first finds show a defined way and an awareness of using these characters.

I am sorry, but a play on words was necessary with this happy news! There has been a huge discovery in terms of runestones, and I feel it is my obligation and big pleasure to provide you guys with what we know so far about it!

Every now and then, scientists make huge discoveries that throw everything written into history books straight out of the window. What was found in Svingerud, Norway in 2021 is such a discovery.

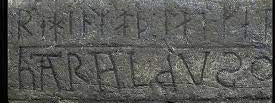

The archaeologists had a task of conducting a dig of a grave field found in Svingerud by the Tyrifjord. In one of the graves containing burned bones and charcoal, they also found a stone. A runestone. Thanks to science and the lovely C-14 method, the archaeologists could successfully date the burned bones and charcoal found next to this stone. The grave’s insides are dated to around the years 0-250 A.D. This runestone is around 2000 years old. Which makes it the oldest runestone ever to be found (with proof of its age). It is named after its place of origin and has the name the Svingerudstone.

The archaeologists in Norway have translated the rune carving into “Idiberug”, which is speculated to be a woman's name, or maybe a family name. There is also a peculiar ᛒ-rune in this carving, with 2 ᛒ on top of each other. There’s also different patterns carved on the stone here and there. Maybe this is the work of one person or several, maybe it's made for teaching purposes or as some kind of game? Furthermore, the stones’ ᛖ-rune is earlier thought to have been used as an E-sound on runestones from the 400’s, which this stone again disproves.

Earlier research has presented the 300-400’s as the introduction of runestones in Scandinavia, which the Svingerudstone beats with many years. This new find has knocked the history books over and history now needs to be rewritten.

We are all anxiously awaiting the experts' new interpretations and conclusions about these new finds and their context.

Theories implies that traveling and the need for broader communication might have been the indicators for these changes. A society where you can communicate is a society that expands culturally. If a society can also add characters in order to communicate, that’s a sign of an expanding community and dynamic times taking form.

The next big change regarding the Nordic language and the runes came during the medieval times. The medieval runes were made to fit the Latin alphabet, so new runes were created in order to have the same number of runes as Latin letters. All of these different looking runes were not included in the rune row however, so even if the runes expanded in number, the official number of futhark runes kept on being 16, like in the Viking age.

When it comes to numbers and having a system for that, as with most things in ancient Scandinavia, there is no tutorial of how that system worked documented down anywhere as far as we know of.

What we do know however is that the iron age Scandinavians were successful in selling and trading, which shows that there must indeed been a system in place to keep track of various tasks. Furthermore; it is a necessity to use counting when it comes to everyday tasks such as smithing, weaving and cooking. There has been many grave goods directly connected to merchant activities such as weights and scales with origins from Iron Age Scandinavia (in for example the Viking age city of Birka and on the island of Gotland).

Other evidence of that the Iron Age Scandinavians had some kind of numbering system can be found on runestones. On the “Runestone in Stora Ek”, county of Västergötland, Sweden. There is a carved down story about a father honouring his dead son. The runestone further covers information on what this father is inheriting from his son, which is 3 farmsteads and 30 coins to gather from a man named Erik. On this stone the 3 is carved as “þria” and the 30 is carved as “þria tiugu”. These words are old Norse for three and three and ten.

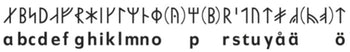

So what is a FUTHARK?

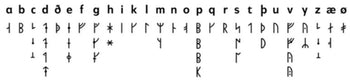

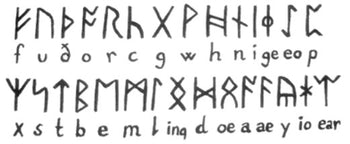

A futhark is the collection of rune characters from a specific era. It works easily explained as an alphabet, where the characters come in a specific order (which can vary here and there). The expression “futhark” is used because of the six first runes of these “alphabets”, they spell out ᚠᚢᚦᚨᚱᚲ (or ᚠᚢᚦᛅᚱᚴ ) which translates into “futhark”.

How do we know which order the runes of the futharks are written in?

Because of various archaeological finds such as the Kylver-stone (Sweden), the Vadstena-bracteate (Sweden), and the Grumpa-bracteate (Sweden). On all of these finds the elder futhark is written down in a specific order. The Kylver-stone (4th century) is the oldest find of a fully carved down elder futhark. The oldest find containing younger futhark runes is quite macabre.

It is the skull fragment from Ribe (Denmark), where the younger futhark runes are carved on the inside of a human skull (8th century). The oldest find of the complete younger futhark can however be seen on the Gørlev stone (Denmark), this stone is from the 9th century.

It is theorised that these runes came from Frisia (what is now parts of Germany and the Netherlands) to the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, hence they are also called Anglo-Frisian runes.

The Futhorc takes different shapes depending on location and point in time.

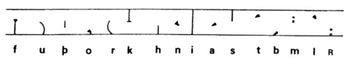

These types of runes are mostly found in Hälsingland, Sweden. They are mostly found on stones. Wood carvings with these runes are very few.

The Short-twig runes were also commonly used in Norway (Oseberg ship, 9th century).

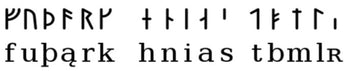

Believe it or not, but the beardy faces you can see on the wooden stick (late 11th century, Bergen, Norway) are runes. The beard-staves to the left represents where in the Futhark the rune belongs, and the beard-staves to the right represents which one of these runes of the family it is more specifically. The same principle can be used on other secret runes. It is however very hard to read these types of runes and they are absolutely for the more hardcore rune-enthusiast to decipher.

nine whole days and nights,

stabbed with a spear, offered to Odin,

myself to mine own self given,

high on that Tree of which none hath heard

from what roots it rises.

None refreshed me ever with

food or drink,

I peered right down in the deep;

crying aloud I lifted the Runes

then back I fell from thence”

– Odin, Hávamál

The Hávamál is a collection of old Norse wisdom that can be found in the Poetic Edda written down during the 13th century. It is however theorised that its content is much older and that its tales have been a part of the oral tradition in Scandinavia before it was ever written down.

In the poems we are told that Odin was the one to give the runes to the humans of Midgard after discovering their secrets when he hung from the worldtree Yggdrasil.

If these tales are much older than the 13th century, it is possible that the people living through the 7th and 8th centuries didn’t know either where the runes came from originally, and these stories could be an expression of that.

Especially when the earliest form of runes might have been difficult to understand as well for them, since the evolution of the language drastically had changed at a fast pace.

The Nolebystone and Sparlösastone (Sweden) are two of these runestones whose carvings mention how the runes are originating from the gods.

To understand why the runes are not used as the common style of writing (carving) anymore we must understand two things:

- What the runes were mainly used for

- What went on in the society during the 11th and 12th centuries in Scandinavia

Every great era must end eventually, and this also meant that the people in Scandinavia stopped raising runestones during the 11th and 12th century to honour their deceased loved ones.

Before the 11th century it was more common to raise a runestone close to different roads and paths where people would easily see them. The bodies of the deceased were often buried in a burial field close by to the farm.

Somewhere during the early 11th century and during the 12th century the Scandinavians, in different capacities, stopped burying their loved ones in the burial fields. The dead were instead brought to the cemetery. In a cemetery the deceased were often given a tombstone instead of a raised runestone near a road.

Absolutely not the case! Even though the runestones and burial ceremonies changed during the early medieval times the usage of runes didn’t decrease. Instead of carving runestones, the carving continued with different objects, some made out of wood. There were messages being sent back and forth, secrets shared, prayers carved down and the names of the owners of different tools.

However – wooden materials aren’t spared by time passing by as well as stones. So not many of these wooden objects have been found. There have been many finds of medieval messages carved in runes made on metal-, horn- and bone- objects.

It took a couple hundreds of years for the Latin alphabet to become the norm in Scandinavia. When Christianity in Scandinavia became more and more common during the 10th, 11th and 12th century, so did the art of writing the much softer shaped Latin letters on parchment.

The exceptions

There is no period in time that is completely black and white, this also goes for the transition from runes to Latin letters. As earlier mentioned there is something called the Dal-runes used in Dalarna (Sweden) up until the 19th century. These runes were mixed with the Latin letters and had different shapes than the medieval runes.

Rune carving was also spared longer on the island of Gotland (Sweden) and in Iceland. This tradition was upheld until around the 16th century.

Believe it or not, the usage of runes never completely went away and is on the rise again. There have been more modern usages of the runes. Even though we are having a hard time pinpointing where they came from, we can undoubtedly talk about where they have been recently.

The names of the runes however originate from rune poems that have been saved from England, Norway and Iceland. These rune poems could originate from different points in time, we will be transparent about what we know and what we have no idea about so far (2021 AD).

That copy from 1705 is the base of what we know about the Old English rune poem today. It contains 16 similar runes to the other two poems, 8 elder futhark runes and 5 Anglo-Saxon runes (these 5 have nothing to do with Scandinavian runes at all).

Now when we have the background of what these poems are, let’s talk about the names of these runes. It seems like just as when children today use rhymes to remember the alphabet, humans back in the day used rhymes to remember the sounds of the runes.

These poems could connect the ᛋ-rune (s) with the word sól (sun) like this:

“Sól er skýja skjöldr, ok skínandi röðull, ok ísa aldrtregi” – “Sun shield of the clouds and shining ray and destroyer of ice”.

The rune is followed with a poem whose first word starts with the same sound of the mentioned rune. If there were other local poems going around depending on dialect differences, we don’t know. Since these are the poems we have to rely on in today’s world, the runes have been named thereafter.

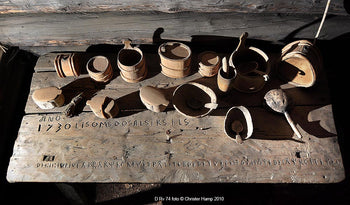

In some of these calendars Christian holidays are included and some are without holidays. These calendars have been carved on horns, wood and bone. The oldest find of one calendar is a so-called “rune stave” from the 13th century. This stave was found in Nyköping, Sweden.

However, both in Sweden and Denmark this exact sequence of runes has been found on stones. On the Gørlev stone (Denmark) the carver makes sure to mention, after this repetitive sequence of runes, that “I placed the runes right/in order”. On the Ledsberg stone (Sweden) this sequence shows up yet again.

Tistel-mistel-kistel are the words you get from deciphering the sequence (these are a form of hidden runes).

It is theorised that the tistel-mistel-kistel sequence has to do with spell work. What the function of this spell would have had is discussed. Maybe it is to keep the deceased safe from graverobbers (there are other examples of curses written on runestones where the carver is threatening graverobbers), or maybe as protection to keep the deceased from walking again. After all, no one wants to have a draugr at their door.'

In Norway there is a beautiful stave church in Borgund, which was built somewhere around the 12th century. Apart from that this church is beautiful inside and out, it also contains four different variations of the tistel-mistel-kistel sequence. One of them is carved into logs of the church, and it spells out with runes: “Tistil mistil ok hn thirithi thistil”, this translates to “Tistel, mistel, and the third thistel”.

Why would this “spell” be found in a church?

The answer might be underneath a loose stone, which was found on the church’s floor. It was by the looks of it a place where women buried unwanted children. They were placed into the church in small chests, under the floor, and maybe the tistel-mistel-kistel above their hidden away bodies would give them peace?

When it comes to runes that are of the elder futhark, it is easy to apply a magic component to them simply because the meaning and use of these words has fallen away and are now covered in mystery.

It has been theorised that the end of the “Lindholmenamuletten” could have meant “öl” (which is Scandinavian ale), or a word that is used for protection. Alu is also found on the famous “Rökrunestone” found in Sweden, a stone also translated to include some magical components to the story it tells. Another example is a small soft, palm sized runestone fragment that has been carved with a knife and the runecarving is to be read from the right to left, which is inverted to how you usually read runes. This small runestone is named “VG134” and has been loosely translated into “aaaaaaaa alu h”, which is mentioned by runologists as very speculative since the runes are so old, but also mentions that it could have to do with the magical runecarving of Alu. Where exactly the beginning of the use of Alu as a magical spell is hard to pinpoint, there is only more modern sources stating that it is a “well known” magical rhythm of runes, where the magic has sneaked into these runes or what their translation is besides “ale” or being “tied to magic” is hard to know. It is all a big historical riddle.

Eril, Erillaz, ErillaR are different ways to carve what is believed to be the same expression. This word is found on carvings on runestones as well as bone-amulets from the Scandinavian migration period. Since the elder futhark is made in such an old language, many if the translations are somewhat impossible to get 100% correct. But that has never held the experts back from trying.

Eril has been translated to mean rune-master or an ancient expression for someone withholding magical powers (like a wizard or shaman). It is however more likely it has ties to the proto-germanic word for “jarl” (or the Anglo-Saxon “eorl”) which might indicate it has to do with military status.

An example where you can find Erillaz is the “Järsbergsstenen” in the country of Värmland, Sweden. Another example is of the more macabre sort, it is the “Lindholm amulet”, where the runes carved upon bone reads:

ek erilaz sawilagaz hateka :

aaaaaaaazzznnn-bmuttt : alu”

The translation has been deciphered into: “I, eril, named Sawilagar. ... ... ale”, which again – this type of carving is a bit too old for us to be completely certain of it’s meaning. However, how this carving ends is what out next section is about.

Now is a perfect moment to bring up facts and what we do know about rune magic. There are not reliable and authentic sources older than the viking age or the medieval times about rune magic. So those are the sources we have to keep in mind when talking about these things. When it comes to the elder futhark and the migration period we have no reliable source material. The magical runes that have been hidden away on the inside of clothes, carved on door frames, or carved on small wooden chips - looks far from the usual runes.Here we have examples of magical takes on ᚦ, ᚼ and ᛏ.

Blótspónn included runes being painted on wooden pawns in visible body fluids, such as blood.

Before they were to be used they would include a full futhark (so at least 16 pawns), and then also some extra characters depending on who and what the purpose was. These pawns were then thrown and from there the ritual would follow.

It is wiser to say that we know less than more when it comes to these types of things, just because the sources are so limited. In Tacitus Germania (written around the 1st century) there is a mention of activities, much like the blótspónn, going on in Germany around the 1st century:

Now to the small part about bind runes. Bind runes can be found at a couple of rune carvings. They are often confused with the Icelandic Galdrastafir (magical staves). Galdrastafirs are not runes or bind runes. A bind rune is a rune that has two runes merged into one. As for example on a runestone in Bolum (Sweden) where ᛅ + ᛒ turn into one rune, a bind rune.

When writing about the modern usage of runes, we have to address the big, pink, tooting elephant in the room – the modern political use of them.

It does not often pass anyone by; there was an intense usage of runes during WW2 (1939-1945). Amongst other ones, the ᛋ rune and the ᛟ has been used heavily in different forms and ways during these times. Some quirks has also been added to these runes (as is the case with the ᛟ with two wings added at its bottom) which has created new forms of symbols. These symbols do not have a longer running history than from this point in time during and after World War 2.

It is therefore important to know the difference between historical futhark runes and newer adaptations of them. This has also inspired more modern political movements to use runes to promote their own agendas and ideologies. ᛘ and ᛏ are also runes that has lately been used for these purposes. No matter who these people are or what they promote, one thing is fact – no one owns the runes. Education will always be the solution to end misconceptions and mistakes to these things.

The big mix of Ragnar Lothbrok, assassins and mystical music.

The hit TV-series “Vikings” tells the tale about Ragnar Lothbrok and his adventures. Anyone who has an interest in Norse history will have heard about this series, and probably have one or two things to say about the historical accuracy of the show’s different elements. Even though the series does not give us anything in terms of runestones, it does display runes in different ways. The most noticeable usage of the runes in this series are the big runic tattoos running across the bodies of these TV-vikings. So the question that many get from watching these types of shows is

The honest answer is that we do not know. There has been no finds from the 8th - 11th centuries to give credit to this. However, there is an account about tattooed northerners by the Arabic observer Ibn Fadlan (10th century). He notes down in his Risala:

There is however no clear mention of runes in this encounter. What we do know is that humans during this time made “teeth tattoos'”, which meant that they carved different lines on their teeth.

Recently a game called “Assassin's creed – Valhalla” launched (2020 AD). In this game you play as the viking hero Eivor, whose mission is to lead her/his clan of Norwegian vikings to the lands of the Anglo-Saxons. This game has the magical approach to runes. In the game you can find different gems with runes, and they will with their magical powers upgrade your armor and weapons.

Remember the Icelandic rune poem? - The Icelandic rune poem is what makes out the lyrics to the band Heilung’s hit song “Norupo”. The Norupo song is the 15th century poem word for word, put into a rhythmic beat and song. In the music video they have also included elements of magic and some of the magical takes on runes from Iceland.

Wardruna is yet another band where runes take a central role in the music. They have songs inspired after the rune poems naming for each rune, such as the songs “Fehu” (ᚠ), “Tyr” (ᛏ), “Uruz” (ᚢ) and “Raido” (ᚱ) to name a few.

No one can deny the importance of social media today. It plays a huge role in spreading a sense of community, knowledge and curiosity when it comes to the runes.

A big part of the community online who dabbles with the runes are often very creative and many are different forms of crafters and creators. Just as this page focuses on design and jewellery, many crafters focus on a modernised way of spreading and creating - with help of the runes.

Be it woodcarvers, tattoo artists, photographers, makeup artists, illustrators, musicians, writers, or any other creative ambition – the “norse / history” community online does its part in keeping the runes alive in today's world. Historically accurate or not, it creates a new historical use for them for the future which is filled with creativity and positivity.

A quick mention of modern runestones.

The tradition of raising runestones might have ended somewhere during the early medieval era, doesn’t mean it remained so. There are a lot of examples all throughout Europe of modern runestones and replicas placed in various countries. This new way of raising runestones also plays a part in keeping this tradition alive. Thousands of years from now on, maybe these runes on these stones will tell the future of us and who we were.

We will publish all the sources used for writing this article, some of which are in Swedish and not English. The goal with this article is to give a fair and informed image of what the runes are and how they have been and are being used. We have been transparent with what is known and what lacks when it comes to source material. All speculations and theories are explained as such, and it should be taken in consideration that these theories might not be the true facts.

I would like to thank all of you who have made it this far – Skål and thank you for your time.

Best wishes

– Elin aka MooseLady

Very awesome info. Coming from someone who never knew any of this before and now has a greater understanding and curiosity for runes.

Immersive, entertaining and informative. Thanks for your hard work! I’m now growing a huge interest in these subjects, coming from a background in language, education and history.

The word “harja” that was carved into a comb probably doesn’t even refer to the owner. Harja is a Finnish word and literally means comb. So, I’d say that a Finn was in the are back then and left behind their comb. Of course I’m not a professional, but Finnish is my first language, so…

I was given a rune symbol on a rectangular stone of what may be red jasper, with corners cut off , the rune is like a capital N with a dropped centre bar. Intuitively I don’t like it and have never worn it, what is it’s meaning and proper way to dispose of it? Thankyou in advance. a

Most helpful site…trying to translate runes cut into the handle of a weapon and would appreciate your help if I sent images.

Your sharing of knowledge is a welcome and invaluable resource, keep up the amazing work!

I’ve had my first name put into runes on a horn, and I cannot relate to them only 3 seem to be right. I’ve never heard of the runes the company say they are. So I’m jot convinced they are right. Can you help in any way. I’ve looked at all you have pictured but they are not there, they say the runes are 750c ?

Thank you for this great gift!

thank you kindred spirit sister for honoring the past and forefathers , ive nearly completed a viking hall (shed) australia and will burn runes into the wood on out behalf and the Gods thankyou

Awesome job! Keep up the work. The world needs you!

ja

Thanks

I want more

Well done an I tip my hat…. I have enjoyed the knowledge, insight an views that this site an the last author the only way to keep a language or system alive is to use it an share what we have learned or saw or felt. I have been more intrigued then ever by the power one can involve with a letter or a symbol or design an how the common core values some do not need a bunch of extra shit an to the point…🤷💪🤘… These are the way fuckin runestones look like to the general population me guilty as charged… When in a world of energy when they claim time is the killer of all but it lives forever in the cloud 🌨️☁️…. The fuck planet am I on!?!?! I lose my passwords an email once a week an your gonna tell me “forever” I call bullshits give me a ball peen hammer a diesel stick welder an an compressed gas of the fire type…. I think i got a plan for a “cloud” so brick an mortar pen an paper hammer an chisel… Leave your mark or your story or plan or the respect’s for the kids to come. Because the only thing worse then death for a man of honor is to be dishonored…(substitute man for woman an if ya can’t figure out to stand or sit to piss) Not sorry life sucks… But leave a positive uplifting one an build up… Not down as we are all equal an only have our “word” or respect or trust an what you do with it is up to you…the negativity downward will never stop so build a ladder with a loved one a reach for the stars an leave a happy positive uplifting message… please 🤔🤬😊💜…❄️🛶❄️🤢🤢❄️👼*️⃣🍽️🛶👼♎… I prefer the younger futhark version much better an the feel an look is gonna be all the redheads running around the “family tree”…. Heritage an family need to be instilled an handed down like physically sometimes as to NOT FORGET THE MESSAGE…. Keep all runes an forms of communication open as to not lose the knowledge!!! (End rant)

wonderfully written and so informative ! Thank you for putting this together.

This is one of the best resources I’ve found for no nonsense information on runes. I love that you’ve made it both informative and attractively presented. In particular, I appreciated the compact way you presented information, using tables where appropriate. (And the “accordion” sections for the Rune Poems was a great touch!)

Amazing job, I am extremely thankful, that is a pill of knowledge that you want to take right away!

My grandfather died recently and this article has inspired me to make a ru estone in his honor.

This is one of the best runestone resources I have run across. Thank you for not speculating and keeping to the evidence, it’s extremely helpful.

I have found that the Anglo-Saxon runepoem had some differences in connotation and even meanings for some of the runes. Specifically, Fehu/Wealth, which appears in the Icelandic to have the connotation of greed whereas the Anglo-Saxon seems to present it as prosperity; Thurisaz translated as Thorn instead of Giant; and Kaunaz/Kannaz, with the completely different translation of Torch instead of Ulcer, naturally with completely opposite representations of meaning. Is there any evidence to say why these changes occurred? I have a couple hypotheses but I only have the poems themselves as evidence. Thank you!!

I am fascinated by your work! I learned a lot from your work, and I hope you are continuing to study the Runes. I have traveled to Sweden several times and feel a strong connection to it. Thank you so much!

The dark comedy show the Norsemen (Netflix, 3 seasons) had a running gag with characters using rune sticks to tell jokes or gossip, and were most often read while sitting on the sh*tting log. I’m now curious which rune set was used in the series. Thank you for this resource!

Thank u for the article, learned a lot!

Hello

I have a fortune stick made from buffelo rib by balak tribe of kurdish. And I am trying to get it translated although also looks like some rune vigil. Could you confirm this can email a picture of the antique. I am very interested if it is a rune calender.

Very interesting! Language is always so fascinating

Thank you so much for the amazing work you’ve done.